Cannabis was controversial long before it came to the USA.

If you Google the question, “why was marijuana made illegal?” you will find many articles on the subject, most of which start the story in early 1900’s America and focus on Harry Anslinger, the Marihuana Tax Act, racism, and perhaps some wild industrial conspiracy theories.

What these versions of the story fail to capture is that cannabis prohibition was international and did not begin in the United States. And while racism was an overwhelming component of American society and law enforcement, this was the segregated Jim Crow era, racism doesn’t explain the origins of cannabis prohibition either since conservative blacks and Mexicans were just as opposed to recreational cannabis use as conservative whites. In fact, Mexico outlawed cannabis drugs in 1920, well ahead of the USA. Hashish, ganja, dagga, indian hemp, marijuana; call it what you want, it’s been controversial for centuries, long before it reached American shores.

Nor is there evidence for any of the conspiracy theories that marijuana prohibition was drummed up to remove fiber hemp from competing with industries like nylon, paper, and cotton. The most common theory is that the Dupont corporation, inventor of nylon, joined forces with newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst who had pulp paper investments to demonize marijuana in order to get fiber hemp off the market.

The reality is that nylon did not compete with hemp and the Dupont corporation had no concerns about cannabis, nor was hemp a factor in the paper markets. Hemp had gone into steep decline after the Civil War due to a lack of demand, high labor costs, and competition from cheap imports. American hemp industries were failing on their own in the early 1900’s and while marijuana prohibition did push them into full collapse, there is no evidence of an industrial conspiracy to make it happen.

Cannabis prohibition was a global phenomenon in the early 20th century, an offshoot of popular international efforts to restrict the non-medical use of opiates, cocaine, and other dangerous drugs. Opium and its derivatives like morphine and heroin were the primary focus for control as addiction was a major scourge in the 19th century, particularly in Asia where the British and other European colonial powers reaped enormous profits through their state opium monopolies. In America, opiate addiction was a big problem among middle class white women who were not allowed into the men’s-only saloons, but could receive laudanum and morphine from their doctors.

The attitude that recreational drug use was a dangerous vice that needed to be restricted was widely shared across races, nations, and cultures. The first drug control treaty was the International Opium Convention of 1912, which was revised and expanded in 1925 to include cannabis and incorporated into the League of Nations.

Cannabis was largely an afterthought in the early drug control negotiations; most countries had no noticeable trade and the medical community described it as mild compared to other drugs. But some countries, including South Africa, Egypt, Turkey, and Greece, had long standing prohibitions and were very concerned about including cannabis in the list of controlled substances.

Cannabis drugs were mostly used by the poor, and some hostility to it has existed in every country where they have a history, generally based on class divisions and perceptions that cannabis caused whatever ills the poor were suffering from, as opposed to recognizing that cannabis is a balm that helps the poor and sick ease their suffering.

The attitude that poor and indigenous people needed to be rescued from their vices by criminalizing their native intoxicating plants; poppy, coca, and cannabis, would become accepted progressive wisdom around the world, even as western pharmaceutical firms were allowed to profitably sell opiates and cocaine based on these same plants. It is an elitist, colonialist attitude that both presumes the superiority of western cultural values (including alcohol consumption) over indigenous cultures, while also criminalizing the day-to-day behavior of the poor and subjecting them to the authority of their colonialist masters.

The Egyptian representative gave an impassioned speech at the 1925 Opium Convention meetings where he repeated many old, prejudiced claims that cannabis causes insanity and violence and provided bogus statistics that hashish was responsible for the majority of cases in the nation’s mental institutions. None of the claims stand up to scrutiny, but they were not challenged at the time. The old myths of cannabis and insanity had largely been debunked by the British govt’s Indian Hemp Drugs Commission Report of 1895 which had arisen from similar claims and calls for prohibition in India.

But the British delegates were in no position to debate because they were the primary target of ire by everyone at the meetings. The British were the world’s largest opium dealers in the 19th century and pushed a very aggressive trade into China despite long standing Chinese objections. Cannabis was included in the 1925 treaty but it was not signed by the United States, because the treaty was not aggressive enough on opiates to satisfy the Americans.

Stepping back in time…

The oldest tales that associate cannabis with violence are nearly a thousand years old. The name ‘assassin’ is believed to be derived from the word ‘hashashin’, the name for a fearsome group of Islamic militants from the 11th century believed to use hashish. The sect occupied the impenetrable mountain fortress of Alamut in Persia where they waged daring attacks on Islamic authorities and Christian crusaders alike for nearly 300 years. Their reputation was known far and wide, and whether they actually used hashish is unknown, but there was a legend that initiates were drugged unconscious and taken into a garden where they awoke to all the pleasures of heaven, only to be drugged again and removed, being told that it was their taste of paradise that was to come if they did their duty. As the dramatic stories of the Assassins were repeated and embellished the connection to hashish was at some point made, and right up to the 20th century was referenced as evidence of the insidious influence of cannabis.

The first modern cannabis prohibition was in Egypt in 1800 when the country was under the French colonial rule of Napoleon’s army. While Napoleon was not personally involved (he had already returned to Europe), his generals worked together with the Islamic religious authorities to ban the sale of hashish and close the hashish parlors that served the local Egyptians and French troops alike. The French troops would bring their taste for hashish back home and in the 1840’s Parisian artists and intellectuals were telling of their experiences with it. The Egyptians for their part would hold firm to cannabis prohibition, as did much of the Islamic world. There were numerous local cannabis prohibitions in the 1800’s; in Brazil, South Africa, Burma, Mexico, and elsewhere.

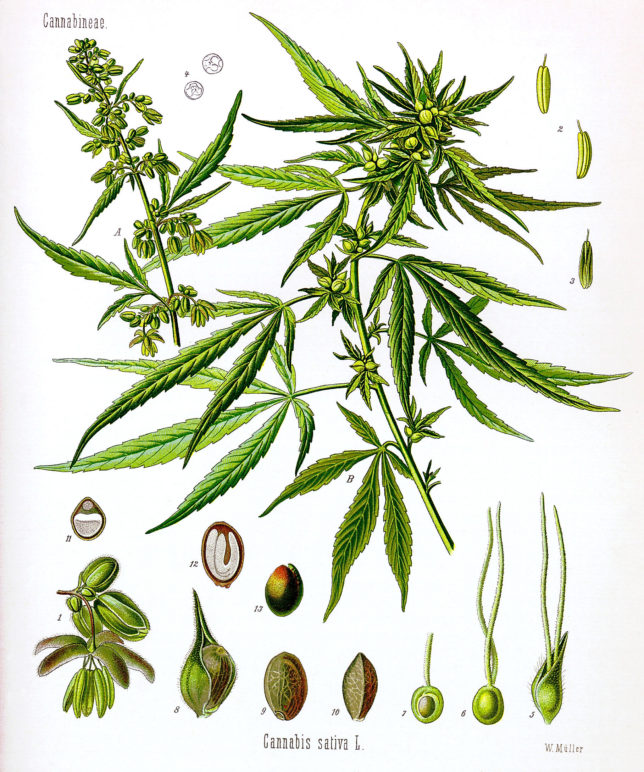

While in America, fiber hemp varieties of cannabis sativa had been cultivated since the 1600’s, but were not known for drugs. European fiber hemp, which we now call industrial hemp, was strategically important during the colonial era because it was needed for shipbuilding. Every colonial power that had a navy was concerned about securing supplies of high-grade hemp for sails, ropes, and rigging, most of which was exported from Russia in those days. The Founding Fathers George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew hemp, and others including Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine wrote of hemp’s virtues and necessity for a modern seagoing nation.

America would never be self sufficient in hemp production though. We relied upon imports because although cannabis thrives in America, growing easily and becoming a weed, the industry was restrained by the high labor costs involved in breaking and processing the durable hemp fibers.

Breaking hemp was considered one of the hardest jobs known to man, and doing it well was highly skilled; the only significant American hemp industry was slave-based in Kentucky and it collapsed after the Civil War. Hemp was widely used for homespun fabric and commercial hemp farming was tried throughout the Midwest, but the results tended to repeat: high labor costs prevented profitability, and the farmers moved onto other crops. Hemp was more profitably grown for seeds that were used for birdseed and oil. Birdseed helped spread wild hemp all over the country and this wild hemp would be later banned by the US government despite having no drug value, and property owners could be arrested if it was found growing on their land.

Drug varieties of cannabis first arrive in the Americas in the 1800’s and were called cannabis indica or Indian hemp, and considered a separate species from cannabis sativa. Native to India and the Middle East, cannabis indica came to the new world through colonial trade and took root in Jamaica, Mexico and elsewhere in the tropical latitudes.

Western doctors discovered its medicinal use in the 1830’s and by mid-century cannabis indica had become a common pharmaceutical in the USA, with most of the early products imported by the British from India. US pharmaceutical firms later grew their own high quality cannabis in the U.S. which they marketed as Cannabis Americana.

In the 19th century smoking cannabis was not common, hashish was typically eaten and the medicines were mostly alcohol tinctures and edible products. Hashish candies were advertised in newspapers and hashish parlors existed in the major east coast cities in the 1880’s, but indulging was a rare and exotic vice. People only started smoking marijuana, rolled into joints the way we do today, in the early 20th century after rolling papers had been invented and the drug varieties firmly established in North America.

The name marijuana comes from Mexico where the plant was hated even more than it was in America. Nineteenth century Mexican elite were truly spooked by cannabis and had their own local restrictions on the plant dating back to the 1850’s. Mexican culture was completely convinced that under some circumstances, marijuana could cause people to erupt into unexplained fits of violence. Insanity caused by intoxication (from any substance) was an accepted legal defense against murder charges for a long time, and it fed the narrative every time someone claimed that marijuana was responsible for their crime. The Mexicans independently originated their own flavor of reefer madness horror stories that closely paralleled claims made by critics in India and Egypt. In all of these cases, cannabis was associated with the lower classes and whatever social pathologies plagued them. Mexico outlawed marijuana in 1920 and has always promoted a firm war on drugs.

The 1910 Mexican Revolution sparked a wave of immigration to the United States that brought both the herb and the superstitions about it, which were quickly seized upon by Jim Crow law enforcement. And it did not help marijuana’s reputation that Pancho Villa’s revolutionary army was known to been fueled by it.

After Pancho Villa’s army seized 800,000 acres and a prized ranch owned by newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst, the magnate’s tabloid papers would never miss an opportunity to portray Mexicans and their marijuana as criminal. Hearst’s tabloid newspapers ran countless reefer madness articles through the 1920’s, portraying marijuana as a source of insanity, violence, race mixing, and sexual immorality.

In addition to flowing over the southern border, cannabis also came by boat into American port cities like New Orleans and New York, both of which would develop rich cannabis cultures tied deeply to music. Marijuana played a critical role in the development of American music and popular culture: jazz, rock & roll, hip-hop, and Hollywood were all fueled by cannabis — and were also denounced by conservatives along the way.

Marijuana smoking was seen by American conservatives as low class, foreign, criminal, and completely outside the norms of respectable white Christian behavior; prohibition was accepted instinctively and without controversy.

In the USA, southern border towns like El Paso, Texas were first to prohibit marijuana as soon as they noticed the practice among new Mexican immigrants. California would be the first state to ban cannabis in 1914. By the time the federal government got into the game in the 1930s, the plant had already been banned in 29 states and some two dozen countries including Canada, Mexico, and the UK.

In Part II we will discuss what was unique about marijuana prohibition in America.